K.R.H. Sonderborg and Michelle-Marie Letelier – what is the connection between two artists from different generations, gender and geography? What warrants the idea to actually present their works together? – Especially at a time which seems to keep apart people from one another that don´t share the same cultural and biographical backgrounds. Between Letelier and Sonderborg, just about everything seems to be different, were it not for both artists´ profound fascination with art and the industrial complex.

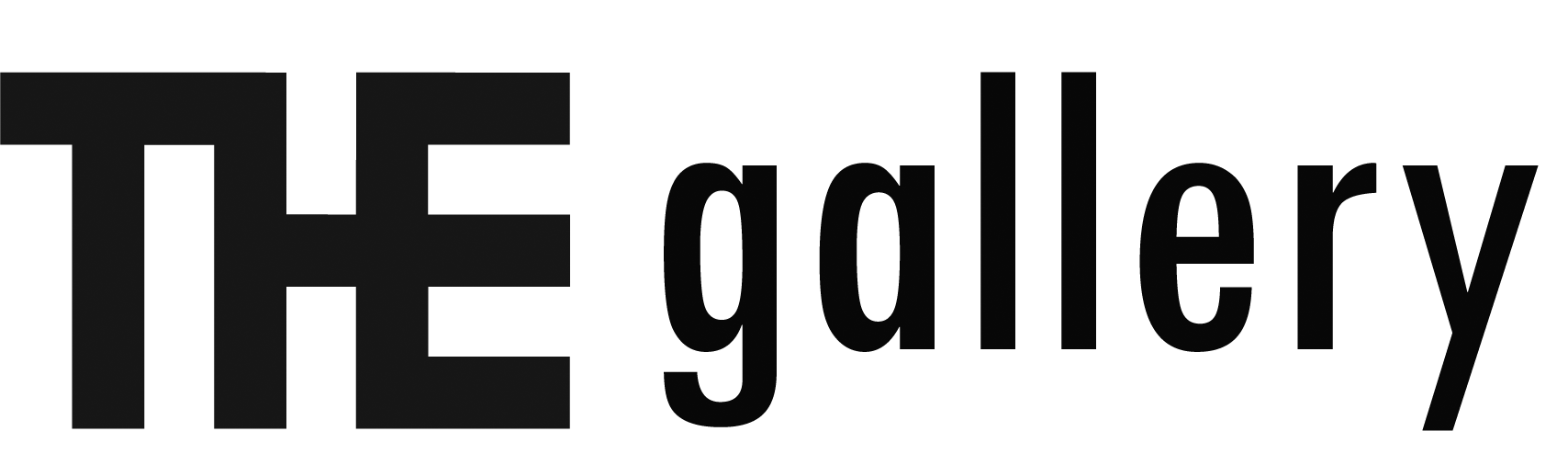

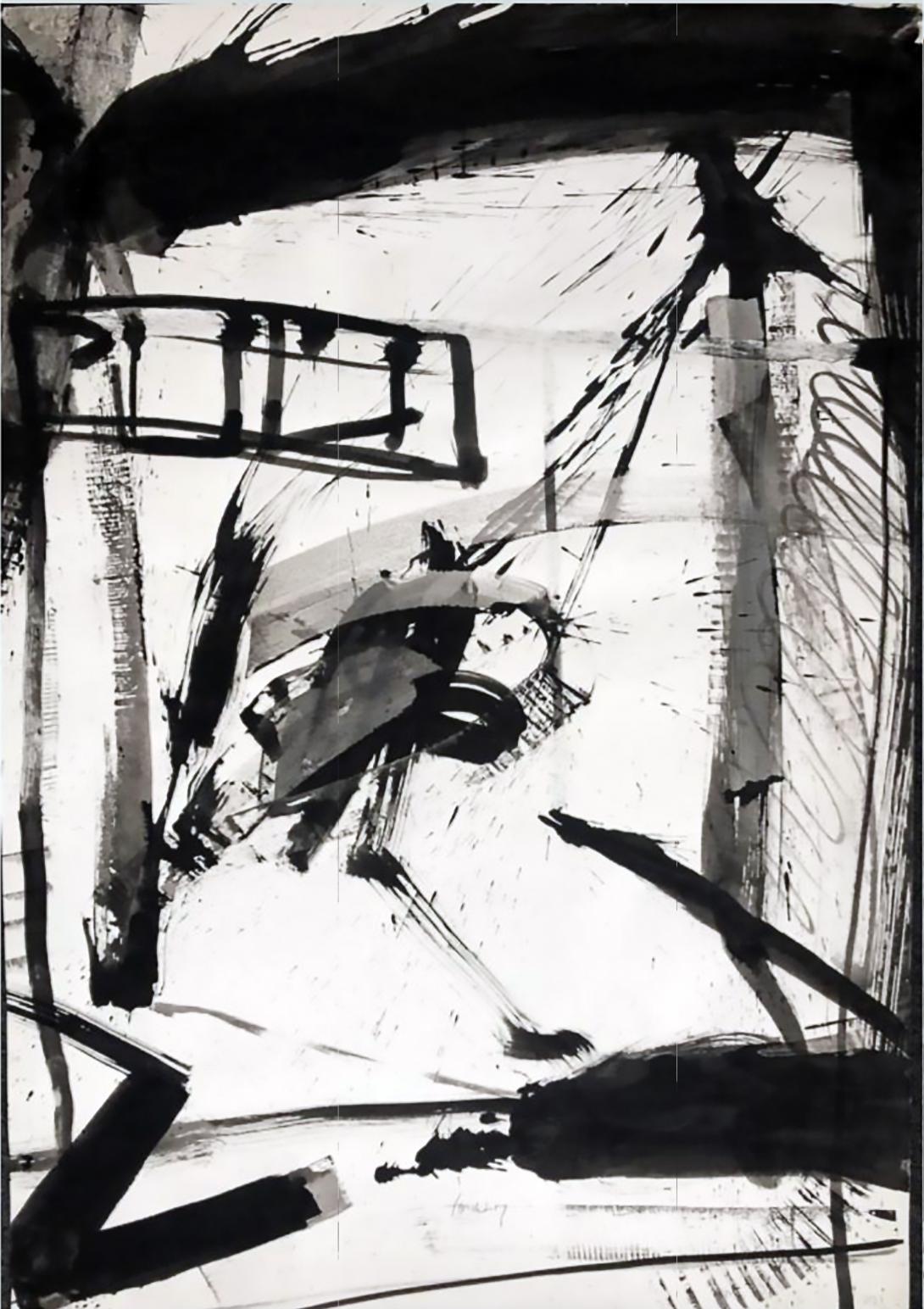

When Karl Rudolf Hoffmann was 18 he was arrested by GESTAPO on the grounds of “Anglophilia” and “sedition” simply for his life-style as the son of a jazz muscian. He had been part of what was called the “Swing Youth” in Hamburg during this time. A crime that could have resulted in up to 3 years in prison and should have barred member form ever studying at a university according to Heinrich Himmler.Sonderborg, as he later called himself after his birth place in Denmark, was freed after 5 months. He did not have to serve in WWII, because he had been born without his right hand. He studied art in Hamburg but disliked the academic approach. Instead his main fascination became the harbor with its cranes, ships and pontons. It were those huge technical structures that he describes as unhumanly big and overwhelming, that became his life-long obsession – the industrial complex beyond the human scale.

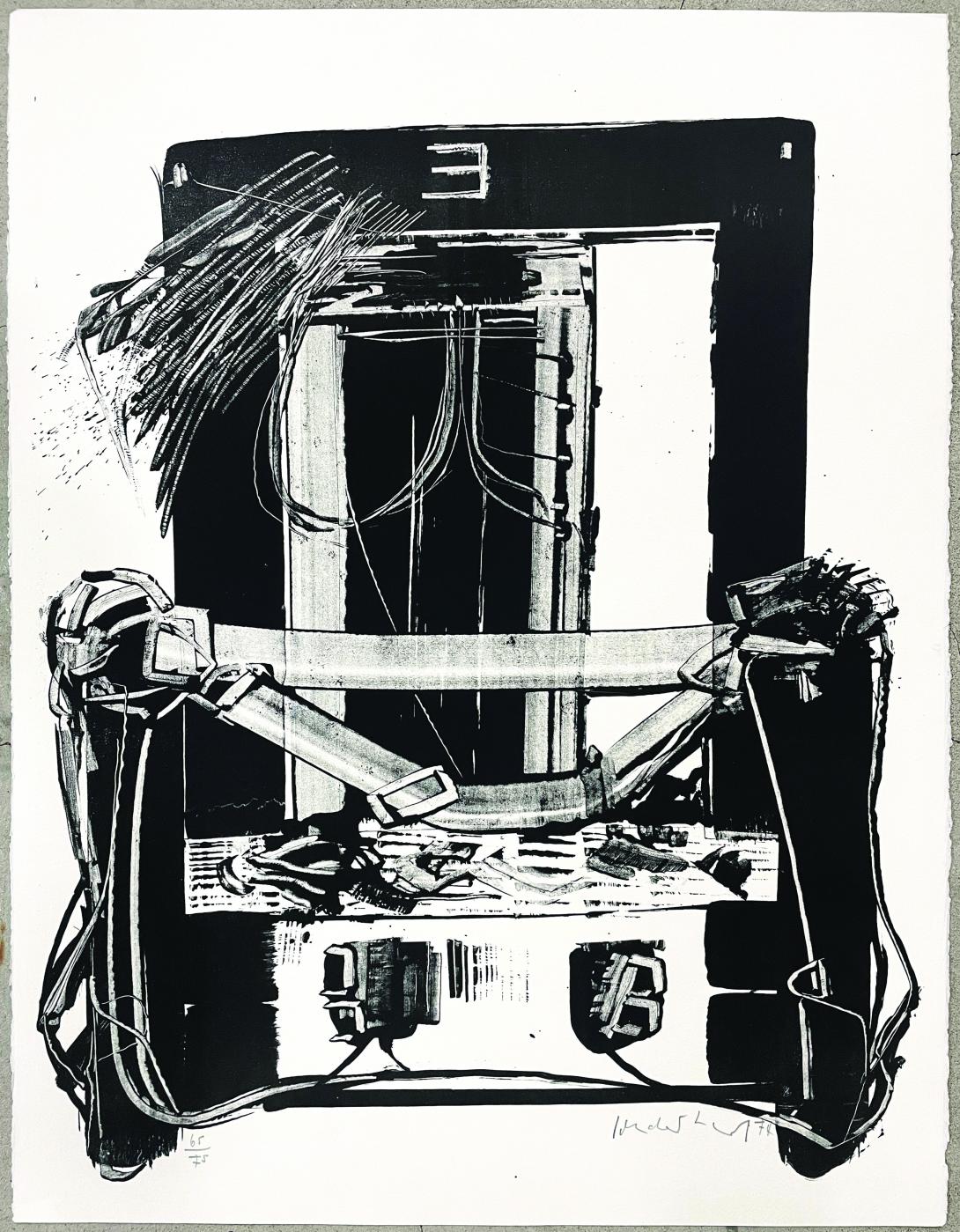

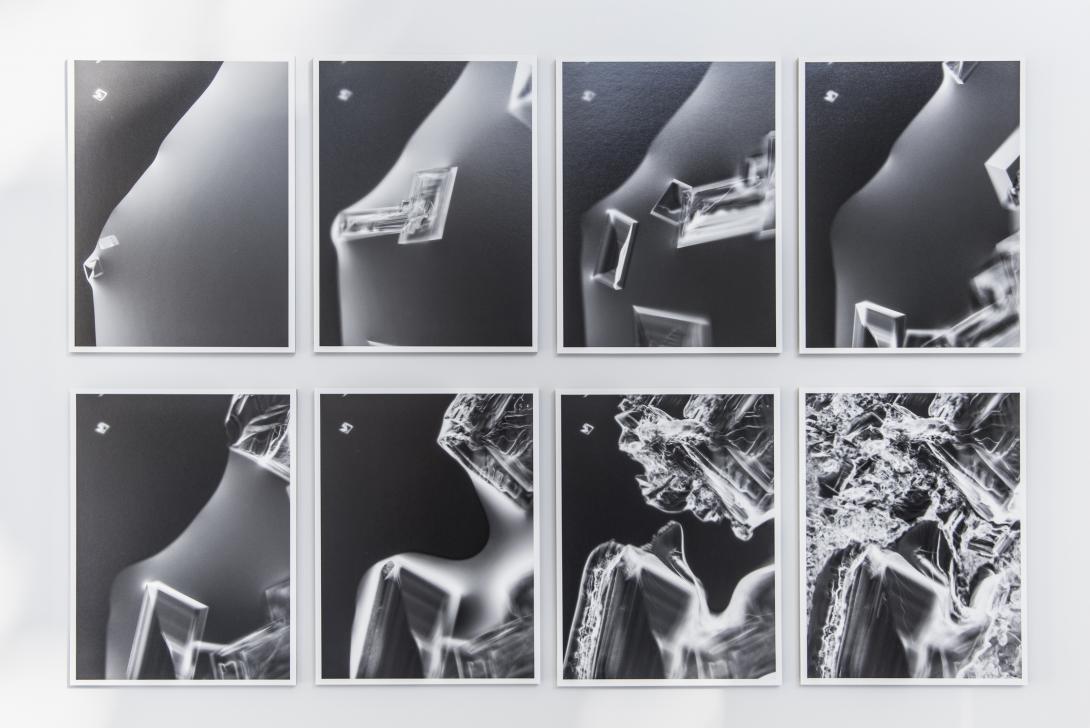

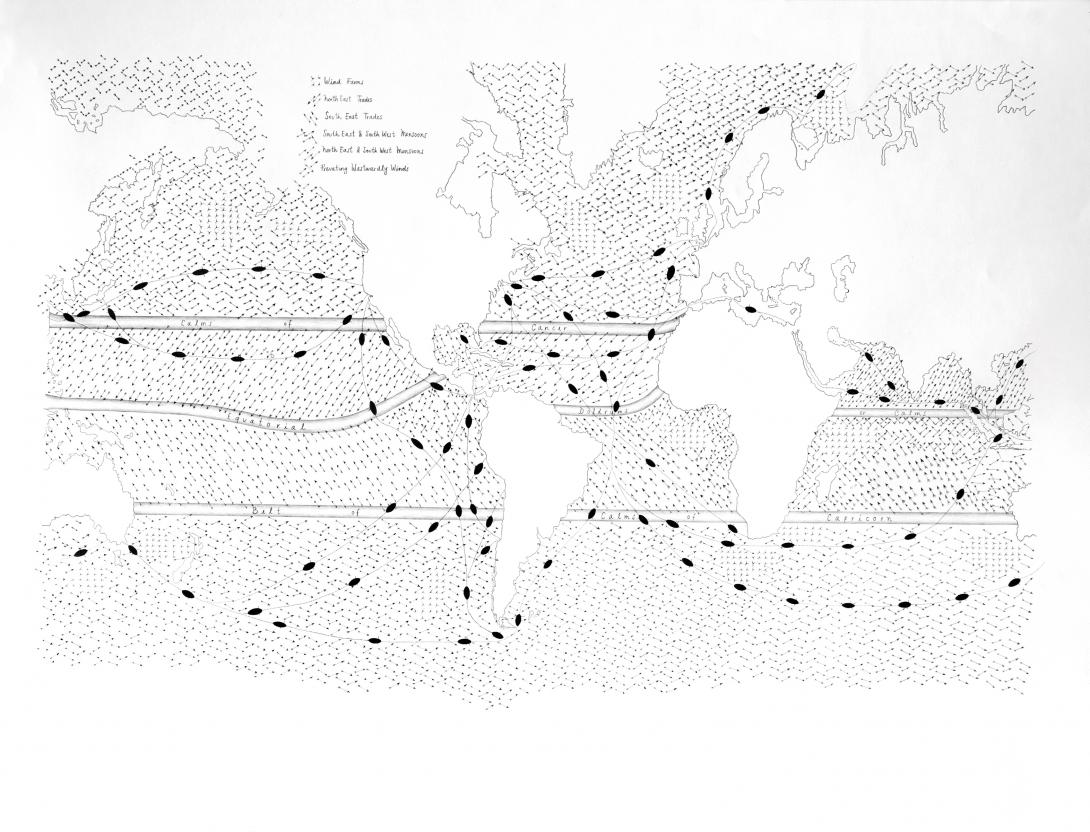

Having been born more than half a century later on the opposite side of the globe, Michelle-Marie Letelier, shares a certain fascination of the overwhelming scale of the industrial complex, its trade routes and global economic exploits. One of her first major drawings is, eerily enough, to some degree reminiscent of the structures that so had impressed the young Sonderborg.

But of course Michelle-Marie did not stop there. Her research goes much deeper into the colonial, techno-economical, sociological and environmental aspects of our exploitation of so-called natural resources.

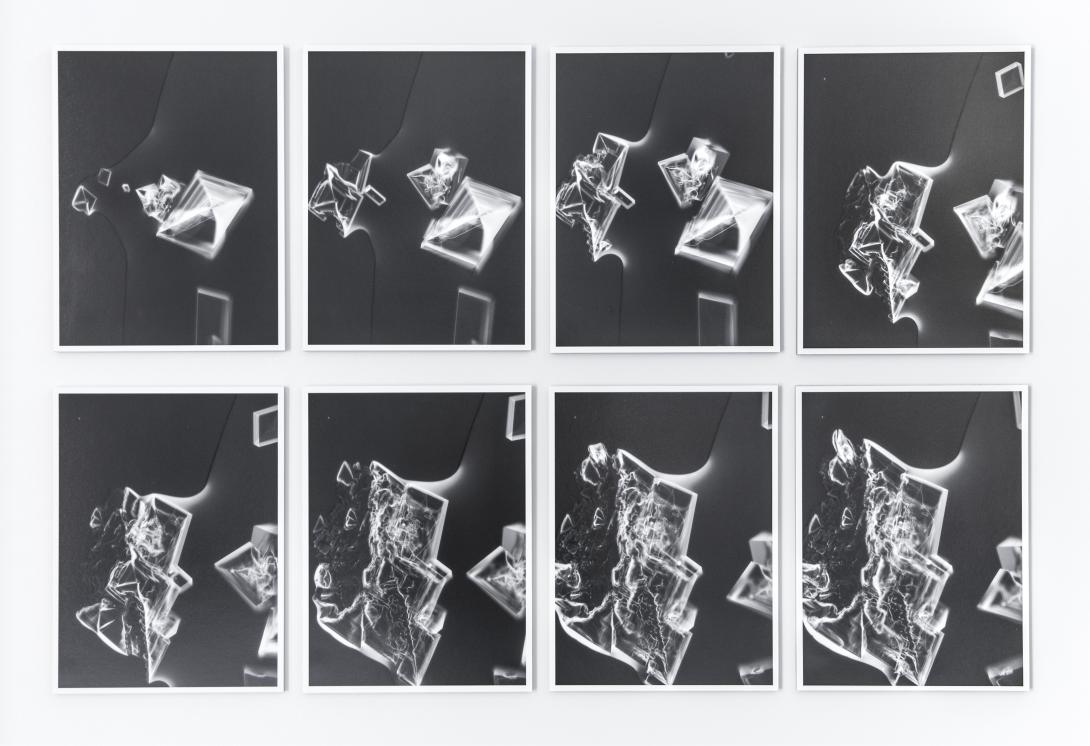

The Bone is an interactive virtual reality experience inside the skull of a wild salmon, where certain elements and narrations are to be discovered. Profoundly inspired by Dr. Martin Lee-Mueller’s book Being Salmon, Being Human, these narrations address ethical and ecological issues related to salmon farming, domestication and coexistence with this species, from a non-anthropocentric, eco-philosophical and indigenous perspective.

Located inside an intermediate world — between deep sea and universe; between present, future or past; between reality, dream or utopia — this skull is a sculptural/architectural construction. The experiencer discovers two otoliths that grow interactively, revealing details about this salmon’s life in the past, as well as reflections towards its cousins: the captive salmons. These reflections are presented as a voice-over from the wild salmon’s perspective; the owner of the skull, in a way of poetic flow of consciousness. The real and virtual space is welcomed by a Yoik sung by Sámi artist Ánde Somby, providing a unique echo and spatiality to this VR, which is physically installed inside an old fishing boat. The materiality of the real old wood sensually echoes the virtual skull, inviting the experiencers to a journey that departs from their position as fisher species, towards the poiesis of the fish’ life.

This artwork has been commissioned by Screen City Biennial, co-produced by Interactive Media Foundation, Oceans21 and Art Republic, co-created with Artificial Rome.

Caliche - Saltpetre

Since 2011 the artist has been working on a massive project exploring the sourcing of “caliche” - saltpetre in Chile. Natural saltpetre — locally known as ‘caliche’; ’sodium nitrate’ in scientific terms — has accumulated on the Atacama Desert probably since the Miocene. While the British shipped their saltpetre from India as a material foundation for their ascent to military superpower, Germany in the 19th century got its saltpetre from Chile. The mining of natural saltpetre fuelled the WWI.

K.R.H. Sonderborg and Michelle-Marie Letelier – what is the connection between two artists from different generations, gender and geography? What warrants the idea to actually present their works together? – Especially at a time which seems to keep apart people from one another that don´t share the same cultural and biographical backgrounds. Between Letelier and Sonderborg, just about everything seems to be different, were it not for both artists´ profound fascination with art and the industrial complex.

When Karl Rudolf Hoffmann was 18 he was arrested by GESTAPO on the grounds of “Anglophilia” and “sedition” simply for his life-style as the son of a jazz muscian. He had been part of what was called the “Swing Youth” in Hamburg during this time. A crime that could have resulted in up to 3 years in prison and should have barred member form ever studying at a university according to Heinrich Himmler.Sonderborg, as he later called himself after his birth place in Denmark, was freed after 5 months. He did not have to serve in WWII, because he had been born without his right hand. He studied art in Hamburg but disliked the academic approach. Instead his main fascination became the harbor with its cranes, ships and pontons. It were those huge technical structures that he describes as unhumanly big and overwhelming, that became his life-long obsession – the industrial complex beyond the human scale.

Having been born more than half a century later on the opposite side of the globe, Michelle-Marie Letelier, shares a certain fascination of the overwhelming scale of the industrial complex, its trade routes and global economic exploits. One of her first major drawings is, eerily enough, to some degree reminiscent of the structures that so had impressed the young Sonderborg.

But of course Michelle-Marie did not stop there. Her research goes much deeper into the colonial, techno-economical, sociological and environmental aspects of our exploitation of so-called natural resources.

The Bone is an interactive virtual reality experience inside the skull of a wild salmon, where certain elements and narrations are to be discovered. Profoundly inspired by Dr. Martin Lee-Mueller’s book Being Salmon, Being Human, these narrations address ethical and ecological issues related to salmon farming, domestication and coexistence with this species, from a non-anthropocentric, eco-philosophical and indigenous perspective.

Located inside an intermediate world — between deep sea and universe; between present, future or past; between reality, dream or utopia — this skull is a sculptural/architectural construction. The experiencer discovers two otoliths that grow interactively, revealing details about this salmon’s life in the past, as well as reflections towards its cousins: the captive salmons. These reflections are presented as a voice-over from the wild salmon’s perspective; the owner of the skull, in a way of poetic flow of consciousness. The real and virtual space is welcomed by a Yoik sung by Sámi artist Ánde Somby, providing a unique echo and spatiality to this VR, which is physically installed inside an old fishing boat. The materiality of the real old wood sensually echoes the virtual skull, inviting the experiencers to a journey that departs from their position as fisher species, towards the poiesis of the fish’ life.

This artwork has been commissioned by Screen City Biennial, co-produced by Interactive Media Foundation, Oceans21 and Art Republic, co-created with Artificial Rome.

Caliche - Saltpetre

Since 2011 the artist has been working on a massive project exploring the sourcing of “caliche” - saltpetre in Chile. Natural saltpetre — locally known as ‘caliche’; ’sodium nitrate’ in scientific terms — has accumulated on the Atacama Desert probably since the Miocene. While the British shipped their saltpetre from India as a material foundation for their ascent to military superpower, Germany in the 19th century got its saltpetre from Chile. The mining of natural saltpetre fuelled the WWI.